It’s difficult to make long-term predictions about the future direction of the games business. We can try to estimate how technology will advance based on past trends, but there’s no way to predict the inventions that will be implemented with that technology, and which of those inventions capture the public’s imagination. One thing that we can safely say is that even when a new development becomes a phenomenal success, games are such a broad medium that the impact will still be effectively localised. Social games for instance, while a billion-dollar industry at this point, have barely registered on the fortunes of traditional PC and console games.

At the moment there is a lot of buzz around the idea of ‘cloud gaming’, as defined by OnLive and Gaikai. OnLive, who have sunk fantastic sums of money into developing (and patenting) real-time video compression technologies, view ‘cloud gaming’ as the ultimate form of DRM. Their prospectus is designed to appeal to the (sadly often accurate) popular caricature of a games publisher: frantically paranoid about the threat of piracy, and resistant to adapting their existing content creation methods to the specific strengths and weaknesses of a new platform. (Consumers and developers, by comparison, seem to factor into OnLive’s plans as little more than incidental.)

Gaikai have a more pragmatic strategy, acknowledging the inherent shortcomings of ‘dumb terminal’ cloud delivery (image compression, lag, bandwidth consumption and congestion) and focusing on integrating their technology into publisher’s websites to allow download-free demos, instead of selling or renting full games. (Note that I haven’t investigated Gaikai as closely as OnLive purely because they’ve not made as much conspicuous noise. Their model might be quite different to how I’ve described it, and might have pros and cons that have escaped my notice.) There are also a number of other companies touting similar technologies, such as OTOY and iSwifter.

What OnLive would like to see (or perhaps, what they need to happen to justify their investment to date) would be for client-side gaming to go away entirely. Obviously this isn’t going to happen. Even if the technology and broadband infrastructure improves over the next decade (and let’s be clear here: right now, OnLive’s offering is only even an option for a tiny niche, and even they must be willing to overlook its shortcomings compared to playing the same games on a $199 console or $499 PC), there will be games that are simply more practical to implement either fully locally (games on mobile devices need to be resilient to network dropouts), or as a more sophisticated remote/local hybrid than just booting up a virtual copy of a DVD game at a server farm somewhere.

Technically, millions of people already play ‘cloud’ games every day – the cloud is where Zynga, Playfish, Runescape, Quake Live et al’s assets live, and the ways in which their clients stream that data are only going to get more sophisticated. Simply chucking a video feed over a network is the clunkiest, least efficient use of the ‘cloud’, and one that will always involve compromises compared to playing locally.

I am trying to avoid the pitfall of assuming the status quo can never be disrupted by new technology. Many pundits scoffed at the original PlayStation, coming as it did at a time when so many consumer electronics white elephants (CD-i, 3DO, LaserActive) were still fresh in their minds. Similarly it was almost impossible to foresee the meteoric rise of the iPhone after years of the sector being dominated by Nokia, Sony Ericsson and Motorola, especially when the App Store didn’t debut until some months later.

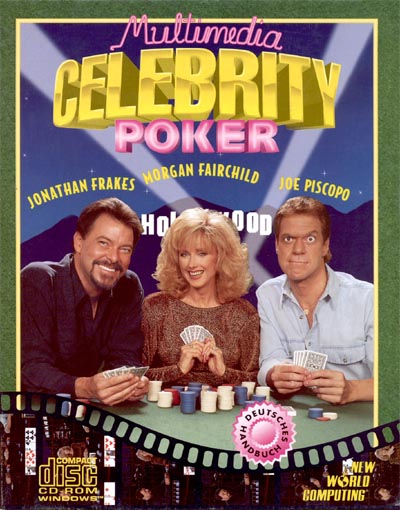

But OnLive doesn’t remind me of the PSX or the iPhone. It reminds me of the execrable “Interactive Movie” boom of the early 1990s, a previous instance when a new technology (CD-ROM) was touted as a panacea by media and technology companies with no previous expertise in the games business. That period is now rightly seen as a skeleton in the industry’s closet. OnLive’s positioning of their technology seems to me as shortsighted as the belief that the CD-ROM’s potential was best realised as a delivery method for cheap, grainy video footage of D-list celebrities.

OnLive’s PR further strengthens this impression, liberally sprinkling their public statements with the kind of bold claims that would make a 1990s “multimedia” guru blush.

The issue of latency has been an albatross for OnLive since their unveiling in 2009. Initial claims were entirely fantastical (such as an encoding overhead of 1ms), later revised to highly optimistic (yet failing to match up with observed evidence), before finally changing tack and claiming they were never going for the hardcode audience anyway (in spite of extensively focusing on hardcore games in their catalogue and having cheesy bro-features like ‘brag clips’), and mainstream gamers wouldn’t notice a bit of lag. It seems to have come as a bit of a shock to them that the more technical quarters of the games press didn’t take their statements at face value.

In spite of this hardcore scepticism, OnLive have found that other, more business-focused parts of the press (VentureBeat, GI.biz, etc.) are easier to blind with science. OnLive’s doom-laden proclamations regarding anything that isn’t based on their technology (consoles, smartphone apps, social games, digital distribution services) are dutifully reported under attention-grabbing headlines.

At E3 this year OnLive cranked their hype machine up to 11. The company’s CEO Steve Perlman demonstrated the system to journalists at the show, while delivering a narrative that at times seemed to employ a kind of Lynchian dream logic to compare OnLive to a series of increasingly disparate phenomena.

Latching on to one incidental element of the Wii U’s implementation to declare 100% functional equivalence made some kind of (laughable, desperate) sense. Obviously any gamer with two brain cells to rub together would see through this claim in a second, but perhaps investors or mainstream media outlets would be fooled? Enthusing about OnLive’s ability to track gameplay metrics (hinting that this was somehow only possible through their system – something which Valve might find amusing) seemed to be an attempt to draw comparisons with Zynga.

But my favourite has to be this bizarre video demonstration of Arkham City’s facial motion capture (provided by OnLive’s sister company Mova). It makes literally no sense whatsoever. Here’s a thing from a prerendered trailer… of a console game… except a console can’t do this… except… but… huh?

What would be the benefit of rendering this in real time? Why would consoles and PCs not be able to do this locally? Motion capture is inherently a process that involves pre-recording animation data then playing it back, which lots of console games (L.A. Noire, Enslaved, Heavy Rain) seem perfectly capable of already. In all of these examples Perlman seems to be clutching at straws (a few hundred milliseconds after they’ve moved somewhere else).

As I see it, OnLive’s biggest problem (other than their love of hype) is one of time-scales. At some point well over five years ago they assessed the then-current market, made some predictions, and locked in to a course based on those predictions that now, untold man-years and millions of dollars later, doesn’t give them much scope for course correction. I think that anyone in that situation would probably have made similar predictions, and ended up with the same problems OnLive now face. Here’s some of the things that wouldn’t have been on OnLive’s radar when they started:

- Wii, Nintendo DS, Nintendo 3DS

- Motion control and touchscreens

- Smartphones going mainstream

- Tablet computers

- Stereoscopic 3D

- No console repeating the market dominance of the PS2

- PC game minimum specs levelling off

- PC game retail dying off

- Steam and digital distribution

- 2D games losing their stigma

- Retail game prices collapsing

- Retail focusing on preowned sales

- Huge crazes for specialised peripherals (guitars, wii fit, etc.)

- Shooters becoming the leading console genre

- Capped broadband packages

- Free-to-play MMOs

- Social media

Back in the early 2000s, when console games stuck rigidly to their RRPs, graphics were king, hardware was prohibitively expensive, most computers were tethered to the desktop and the ‘expanded audience’ hadn’t been tapped, OnLive’s offering probably would have made some kind of sense to consumers. These days we’re spoilt for choice for gaming options at every conceivable price point and level of complexity. The idea of needing to rent games or buy time on some distant ‘luxury’ computer for cost reasons seems as archaic as renting a NeoGeo console for the weekend.

Even arguments OnLive have made in the past two years (regarding the cost of a ‘tricked out’ PC that can run Crysis, or the ‘impossibility’ of tablet computers being able to run Unreal engine games) have dated alarmingly quickly.

To be fair, OnLive have gradually been transitioning their pricing model from “mentally insane” to merely “unattractive”, and I expect that they’ll continue to try to find a suitable model as the technology continues to mature over the next few years. My guess (and it’s a total guess) would be that the consumer offering gradually fades away, and specific markets where the their approach is most suitable (casual games through internet TVs being an obvious one) will be tackled instead, possibly in partnership with licensees who have the appropriate content. A lot of the big publishers of today will probably want to build or buy in solutions that they own and control, as well.

I think the companies that ‘win’ at cloud gaming will be the ones that work with developers and engine licensors to figure out how they can make new experiences possible, rather than those trying to reassure publishers that they can carry on with the same inefficient practices that are increasingly struggling at retail. Selling access to games won’t work for games that are not designed to be experienced like music, TV and movies.

Like FMV, motion controls, achievements, polygons, QTEs, or any other innovation, cloud computing is ultimately just another tool in the toolbox. It doesn’t have to revolutionise every corner of gaming to prove its worth. And it’s not a foregone conclusion that the companies that blaze the trail will ultimately reap the benefits.

Tags: cloud, cloud gaming, commentary, gaikai, hype, jonathan frakes, onlive, predictions, scepticism