In the last couple of years, the line between PC and console gaming has been (in some respects) almost completely erased. The simultaneous release of high profile titles on PC, Xbox 360 and PS3 is becoming the norm. It’s easy to forget that before the mid-1990s, computer and console gaming were completely different worlds – two hobbies running in parallel with very little crossover between them.

While console gamers gawped at Starfox, PC gamers chuckled to themselves and went back to X-Wing. We’d … seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Of course then the Playstation came along and all the fascinating things people had been doing under DOS got swept aside, but for a few short years PC gamers had a legitimate reason to be smug.

Today, the vast majority of development projects are railroaded into long-established genres, known quantities where schedules and budgets can be (usually over-optimistically) drawn up at the outset. Back in the early 1990s, developers and publishers seemed to have no such play book to work from, resulting in a raft of games that were staggeringly ambitious and seemed to have no obvious precedents – games which would be almost inconceivable as commercial ventures today.

Some such games caught the gaming public’s imagination, allowing their creators (such as Sensible, Origin, Bullfrog, or the Bitmap Brothers) to found dynasties and ensuring their games are still widely remembered. Other games (such as Alone in the Dark) didn’t stay the course, but inspired later, more mainstream games (Resident Evil) to secure their place in history as a footnote.

There were still other, equally fascinating games that haven’t survived into posterity.

One such game was Stunt Island, developed by The Assembly Line and published by Disney Software for the PC in 1992. Stunt Island was a game that had the odds for historical recognition stacked against it from the outset. It shipped on six floppies bundled with a 180-page manual and a poster map, pushing its retail price towards £49.99, not a reasonable price for any game, then or now. As far as I’m aware it never saw a budget or CD-ROM re-release, and its status as Disney’s intellectual property has frozen any chances of reviving the franchise stiffer than Walt himself.

As one of the lucky/spendthrift few who did play it the first time around, I still regard it as one of the most impressive pieces of software I’ve ever seen, as well as the main reason I’m so disappointed when each new GTA game fails to implement a demo recording/editing mode.

Stunt Island was the brainchild of Adrian Stephens, a maths guru who had previously worked on the cult Amiga and ST cyberpunk puzzle-cum-shooter thing Interphase (and subsequently worked on projects as diverse as Comix Zone, Sonic X-treme, Vigilante 8, and most recently the True Crime series of GTA-alikes for Activision).

The game operates on two distinct levels. The core of the game is a flight simulator, which allows the player to fly one of 48 Gouraud-shaded aircraft around the titular Island, and to try their hand at flying 32 predefined stunt missions (storming a barn, flying under bridges, parachuting off a building and other such Hollywood action staples). More intriguingly, the game also provides what is essentially a complete virtual studio for producing machinima (eight years before the term was coined).

Creating an original movie in Stunt Island comprises of three main stages (which can be iterated through multiple times depending on the scope of the film and the number of scenes required).

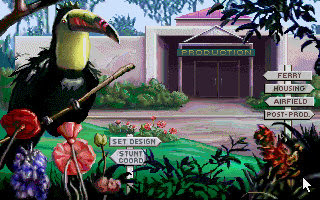

The first port of call is the extremely flexible Set Design mode, which allows the placement of props, vehicles, cameras and trigger objects anywhere on the island, and even allows for some simple scripting to trigger events, switch cameras and direct the movement of entities during the action phase. All of the game’s pre-canned stunt missions were created using this tool, and while it’s slightly cumbersome by modern UI standards, it’s still possible with a bit of patience to build fairly complex scenes.

Once the scene has been set up, the player/user must then ‘fly’ the stunt. (The game’s terminology is heavily geared towards aircraft-based stunts, but in actuality the player’s controls can be bound to any vehicle or prop. They can even just park out of shot and let the cameras capture the scripted actions that they’ve programmed in the Set Design mode.)

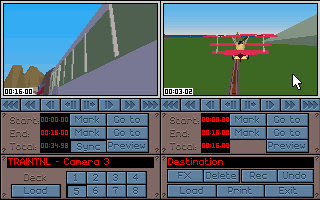

Finally, the footage from each of the (1-8) cameras recording the scene is fed into the Editing Suite, where it can be spliced together into a final cut, and where a soundtrack and visual effects (fades, titles, etc.) can be added. The game shipped with an external player program to allow films to be distributed to people without the full game, and there is evidence that this subsequently happened on a small scale (on AOL and Compuserve mainly, as the game predates the popularisation of the World Wide Web).

Following the movie making process from conception to completion demanded quite a lot of effort on the part of the user, but it was possible to achieve good results, and the process itself taught a lot about movie editing and game scripting. Although most of my own efforts have long since succumbed to hard disk failure, a few Stunt Island epics have latterly made their way onto YouTube. (Unfortunately most of these are rubbish, so you’ll just have to take my word for it that it was possible to make something vaguely watchable.)

Stunt Island was able to realise its extraordinarily ambitious brief thanks to two things. The first was Stephens’ very robust engine technology, which allowed the game to render the (massive) game world as one contiguous map, through the use of a rudimentary Level of Detail system. Interesting scenes in the world were rendered in more detail (for instance zooming in on a city would pop up individual roads and buildings).

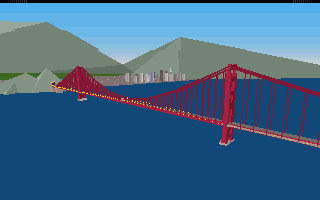

The accompanying map listed the coordinates of dozens of places of interest that were tucked away (including the Golden Gate Bridge, Alcatraz island, St. Andrew’s Castle, Stonehenge, farms, towns, army bases, railroads and aqueducts). Of course by modern standards it looks like how Google Earth might look in the world of Dire Straits’ Money for Nothing video, but at the time it was an impressive technical feat.

The second enabler was that the developers very cleverly limited the scope of what would be simulated within the world. Planes, simple landscapes and military hardware had been the stock in trade of 3D computer games for many years; rendering convincing people (to say nothing of trying to animate them) was a non-starter. Basing the game around traditional Hollywood stunt work (going so far as having quite a lot of in-depth background material and an interview with a Stunt Coordinator in the manual) explained away these limitations quite well.

Very few games have followed in Stunt Island’s footsteps. The dependency on permanent storage and a (cursor-driven) editing mode has until recently been a major obstacle to the development of similar games on consoles. In the PC gaming space, the emphasis on ever-increasing graphical realism and diminishing consumer tastes for games that demand extensive learning and time investment have had a similar effect.

The only game in recent memory even slightly similar has been Lionhead’s The Movies, which rather awkwardly married Bullfrog’s tried and tested Theme Park/Hospital business management formula to the popularity of The Sims series (both as a game and a machinima-creation platform) and sank without trace.

In the wake of the Nintendo DS and Wii, and the rise of the various online distribution platforms (e.g. Steam, Xbox Live Arcade, Playstation Network), there seems to be a more positive attitude to experimentation throughout the industry of late. I believe that in this climate, a canny developer could reinvigorate the “virtual movie studio” concept. Nintendo’s Mii system (as used to great effect in Wii Sports, Wii Play and the upcoming Mario Kart Wii) has shown that gamers aren’t obsessed with photorealism. A “Mii Movie Studio”, supported by a channel on the dashboard (where all Wii users could view and give feedback on user-generated movies), could be huge.

Failing that, there’s always the chance that Rockstar will finally do the right thing with GTA4. We can but dream.

Tags: DOS, Game, game title, Machinima, PC, PC Gaming, Stunt Island