Time once again for a round up of the notable games I played in the last year. 2020 was a pretty solid year for games (if nothing else), although lacking any decisive raising of the bar in the AAA space (except Half-Life Alyx I suppose, which I don’t have the kit to play yet). Still, there were plenty of top tier indie releases to fill the void.

Horace

I’m going to kick things off with Horace because out of everything I played in the last year, this game has been by far the most unfairly overlooked. It’s out on Steam and Nintendo Switch.

Most of the tweets I see mentioning Horace are baffled as to why it hasn’t received more recognition. The sad fact is that by using pixel art and having the words “retro” or “nostalgia” featured anywhere in its marketing, Horace all but guarantees that it will be overlooked by many critics and award programmes (especially in the UK), where games have to be seen to be ceaselessly innovating and threatening the cultural dominance of film and television to be taken seriously. Llamasoft, PuppyGames and HouseMarque can all attest to this. There seems to be a common misconception that anything engaging with the history of the medium must be lightweight and disposable. As such, other than this lovely review by Christian Donlan for Eurogamer, Horace hasn’t made many ripples at all.

Horace is a narrative platformer that tells the life story of Horace, an android designed by a scientist (“The Old Man”) who tries to teach him about the human world by inviting him to live with his family and giving him a more or less normal childhood. The game’s creator (Paul Helman) cites Being There and Jet Set Willy as key influences, and there are also definite shades of John Wyndham (science fiction catastrophes playing out in a mundane English setting), Edward Scissorhands and the more Data-centric episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation thrown into the mix.

The opening chapters serve as a tutorial, confined to the old man’s mansion on an island. We’re introduced to a large cast of central characters including the old man’s wife and their young daughter Heather, their driver, cook, valet and various others whose back stories are revealed over the course of the game.

Horace is introduced to various human pastimes (and likes video games best), starts to win Heather’s trust and understand the other characters’ personalities, and resolves to make it his life’s purpose to pick up one million pieces of junk. (It’s almost like this game has something to say about the life experience of its creator and likely audience? But you don’t climb Existential Crisis Mountain to fight the Depression Monster so perhaps it was being a bit too subtle.)

At a certain point in the story Horace is deactivated and put into storage for several years, during which a calamitous event befalls the world and the characters we meet in the first act are scattered to various locations on the mainland. So Horace sets out into the world to try and piece together what happened. I don’t usually care about spoilers but I’ve tried to keep this all as vague as possible, as a huge part of the appeal of Horace is that you have no idea of the ultimate parameters of the game and the many twists of the story at the outset.

Horace is a genuine fantasia, a flood of ideas woven into a story as expertly as this has every been attempted in a game. It’s in the vein of Wizkid, or Gunstar Heroes or Dynamite Headdy – or rather Dynamite Headdy as it would be if Treasure spent seven years making it, on an exclusive diet of 1970s and 80s British TV. It feels like an improvised series of bedtime stories build with gamestuff.

All of the (hundreds) of cut-scenes in the game are animated using the game’s sprites and narrated with Horace’s flat text-to-speech voice. This seems to be intended to evoke the atmosphere of children’s TV shows, and Horace’s guileless narration of the other characters’ dialogue is frequently used to comedic effect. (I can see how this stylistic choice would put some players off though.)

My understanding is that development of Horace started out in GameMaker and graduated to Unity as Helman’s ideas became more ambitious. For the most part, Horace is mechanically on the level of a 16-bit era platformer, with smooth animation, responsive (albeit twitchy) controls and rudimentary physics.

Early in the game Horace acquires some gravity boots which allow him to walk on surfaces at any orientation, the camera rotating freely to keep him upright. The boots affect Horace’s local gravity (walk up a wall and ‘jump’ off the end and you’ll ‘fall’ at 90 degrees to the ground) but not that of other objects in the world (unless he’s directly holding them). The surfaces of the world are bristling with flames, spikes, conveyor belts and other hazards, but Horace has infinite lives, resulting in gameplay that fans of VVVVVV and Super Meat Boy will feel at home with.

Horace’s long development unfortunately means that its design recalls the time before ‘masocore’ platform gameplay was largely discarded as a terrible idea. Some sections of the game are hair-tearingly difficult, even with infinite lives. (One vitally important tip would be to buy the ‘binoculars’ powerup as soon as it’s offered, as in some gravity-bending later areas half the puzzle is even working out where you’re supposed to be going.)

This is compounded by the stick controls on the Switch version not being very well tuned and the gravity boot mechanic being a shade too sensitive, requiring deft use of the jump button to avoid inadvertently sticking to low ceilings and outcroppings. And the less said about the swimming controls the better. Horace is the closest I’ve come to throwing my Switch out the window. It’s a testament to the quality of the writing that I managed to persevere through the most unfair bits because I was so invested in the characters.

There are more relaxing interludes breaking up the gauntlet of platforming challenges. Aside from the abundant story scenes, there are various optional sidejobs (including sorting post and drying dishes) to earn extra cash, plus lots of secret rooms and caches of junk squirreled away to help Horace get nearer to completing his primary life goal. The game also has a full into-the-screen sprite scaling driving engine, which powers several of the arcade games scattered around the world (pastiches of After Burner and Out Run and numerous others), a few getaway chases, and Horace’s recurring Raymond Briggsian dream of flying above the clouds.

Aside from the punishing difficulty and retro aesthetic, the other thing that might be putting you off trying Horace is the promise of hundreds of pop culture references. It’s true that the game is full of callbacks to (mostly 1970s and 80s) UK television, movies and games. But it’s a long way from being a tedious Ready Player One / Peter Kaye nostalgia-wallow. Key to this is that it never draws attention to the references or expects you to appreciate or even notice them, they’re just an extra garnish for players of a certain age and background. (The same approach taken in series 1 of Spaced.) I’m sure there are many that completely went over my head, being as I am a young person. (Cough.)

Aside from the spoof Thames TV ident that opens proceedings, for the first few hours Horace is the model of restraint when it comes to reference humour. Once you get into the wider quasi-open world, it starts to sneak more and more nonsense in. Most of the humour comes from just how incongruous most of the references are – you just don’t expect to encounter Pat Butcher, Mrs. Slocombe and Reg Hollis from The Bill in any video game. There’s a definite Viz / B3ta (MAD Magazine / Zucker Abrahams Zucker if you’re American) ‘naughty schoolboy’ streak to the gags, with many references seeming to be included to see what they could get past the publisher both in terms of appropriateness and parody protection in copyright law.

As the game is the largely unfiltered product of one mind, there are a couple of ‘edgy’ jokes here and there which probably should have been left on the cutting room floor on taste grounds (again, think B3ta at its least edifying moments), but they’re mercifully rare. Some of the references are also telling of the game’s long gestation – for instance Helman probably didn’t expect Bill & Ted to re-emerge in the pop culture mainstream when naming and modelling a couple of prominent side characters after them, a la Biggs and Wedge.

(Despite appearances this definitely isn’t a game for young kids, by the way – there’s quite a bit of violence, profanity and soft-ish drug use over the course of the story.)

If you can put up with the brutal difficulty and a few rough edges, I’d recommend Horace as probably the best example of a narrative platformer I’ve seen outside of Another World. It’s also probably the best example of a ‘culturally British’ game I’ve seen, concerned as it is with UK games culture, and without a red bus or phone box in sight. (And if you’re wondering, yes, Horace does go skiing.)

Streets of Rage 4

I’ve always been a bit wary when European indie studios announce that they’re reviving a well-loved old Japanese franchise. It can sometimes feel a bit presumptuous – being a lifelong fan of something doesn’t necessarily give you license to make a continuation of it (even if the actual, legal, ‘getting the license’ part seems to often be achievable these days).

I’d heard that LizardCube had done a faithful job with their previous revival game (Wonder Boy: The Dragon’s Trap). But Streets of Rage is a bigger challenge to take on. Streets of Rage 2 has sat at the pinnacle of it’s genre for a quarter century. During the heyday of the scrolling beat-’em-up, nobody managed to top it, not even in the arcades, or on more powerful console hardware. Even the original developers found they didn’t really have anywhere left to go when they were given a bigger ROM cartridge to make Streets of Rage 3 the following year. What could a new Streets of Rage game hope to be, beyond a nostalgic retread? An announcement trailer that seemed styled after a 1980s Saturday morning cartoon did little to assuage our fears.

And yet, somehow, they managed to pull it off. SOR4 feels as faithful a continuation of the series as can be reasonably expected so far removed in time and influences. Looking at the direction that Capcom and SNK went with their fighting game character designs toward the end of the 1990s, you can just about imagine this is what SOR4 would have looked like if Ancient had managed to get it greenlit during the Dreamcast era (and if contemporary commercial pressures hadn’t demanded most 2D franchises make the leap to 3D).

Playing SOR4 as a life-long SOR2 fan is like the moment when The Wizard of Oz switches from black and white to Technicolor. It’s a perfectly accurate mechanical recreation of the original games (so much so that you can even unlock the SOR1-3 versions of all the main playable characters). The original trio of Adam, Axel and Blaze have been redesigned to look a little older but still play the same way, and many enemies from the original games return. The new enemies and bosses added to the roster fit perfectly with the established style – the new antagonists, the Y Twins, nail the ‘aloof Bond villain’ aesthetic that made Mr X. and Shiva so intimidating.

Once again, we have the combination of lush, atmospheric backdrops, driving music and crunchy, ever-readable animation meshing together to carry the player onward. There’s even a bit of a story told through brief cut-scenes between stages, with the triumphant return of Adam Hunter (who hasn’t been a playable character since the first game in 1991) being a particular highlight. The comic book art style (lots of halftone dots and jazzy ink outlines) isn’t distracting, and lets the artists do a lot with what is by modern standards a relatively sparse number of animation frames per character.

You can’t talk about a Streets of Rage game without mentioning the music, and SOR4 acquits itself well on this front too. There are new tunes (incorporating production techniques from the original games’ soundtracks) from Yuzo Koshiro and Motohiro Kawashima, but main composer Olivier Deriviere’s tracks can’t be overlooked either – the themes for the police station and biker bar levels (the latter sounding like nothing so much as Daft Punk and Wizzard getting into a drunken brawl) standing up to repeat listens. There’s even a track by Scattle in there – a nice nod to Hotline Miami’s SOR influences.

In the standard ‘Story’ mode, the player’s lives are replenished after each round and there are infinite continues, allowing the difficulty to be pitched at a level that will offer a meaningful challenge to new players, and adds just enough jeopardy to get them properly invested in learning the nuances of each character.

There’s also an ‘Arcade’ mode which works in the more traditional manner (see how far you can get with a persistent pool of lives and special attacks) which is a great way to dip into the game again once you’ve beaten it a few times and unlocked everything. Getting the difficulty balance right is the key to the whole enterprise – it makes SOR4 feel as exciting as playing (and honing your skills on) a scrolling beat-’em-up in the arcade, without the reliance on frequent cheap deaths.

I do have a few criticisms, but they’re minor. There are a couple of ‘gimmicky’ sequences that require a specific approach to get through without losing loads of health (e.g., the dojo) which break the flow a bit. Some of the cut-scene artwork is perhaps a little bit too close to rough storyboards. And in terms of backgrounds and set-pieces, everything is a little bit too conservative – there’s no particularly amazing Treasure-esque stuff done with parallax, scaling and rotation that you feel the original developers might have tried given access to essentially unlimited hardware power, although the resulting game hits a solid 60fps on all platforms so perhaps it’s unfair to expect too much. And finally, while all the characters have distinct playing styles, they’ve perhaps resulted in Axel being a bit too slow and rubbish by way of contrast, although I don’t know why you’d want to play Axel anyway once you’ve unlocked Adam, the best character.

Overall, SOR4 is a worthy companion piece to SOR2 and is an essential purchase. Five knife-wielding Galsias out of five.

A Monster’s Expedition (Through Puzzling Exhibitions)

Disclosure: I know some of the people involved in this game and the designer/director (Alan) was nice enough to send me a copy.

You’re a monster (and in the game, etc.). Specifically, you’re one of the monsters from previous Draknek game A Good Snowman Is Hard to Build, on a day out exploring a museum dedicated to humans (who we can infer have gone extinct at some time in the past, for reasons possibly related to why the museum is located on a series of tiny islands where England – or ‘Englandland’ in monster parlance – used to be).

On a superficial level, A Monster’s(…) is a bit like (the equally brilliant) Stephen’s Sausage Roll. They’re both games where you explore a series of islands, solving puzzles by pushing and rolling objects around a Sokoban grid, with infinite levels of undo (which you’re encouraged to use often).

Unlike Stephen’s Sausage Roll, the possibility space for solving any given puzzle here isn’t mind-destroyingly enormous. (No disrespect to SSR – it’s a game I love but one I’m resigned to probably never completing.)

Most of the puzzles in AME(TPE) are designed in a way that lets the player intuit the approach they should be taking to get to the solution, based on the situations they’ve already encountered and new rules that can be discovered through experimentation. Sometimes the first step you make on reaching a new island will accidentally cause a new mechanic to be demonstrated to you. Combined with the laid back presentation, the effect is to make the game feel welcoming. While the difficulty level creeps up as the game progresses, it never spikes suddenly or contrives to make the player feel like they’re trespassing in a space reserved for hardcore puzzle heads.

While the core components of the game don’t really change much throughout (the goal of each island – to get logs to specific places to make bridges and rafts – stays more or less the same), every few islands the main ‘path’ will lead you to a different region (or ‘biome’ as the kids say) of the world map. There are also frequent rest stops, puzzle-less islands containing a museum exhibit (typically a mundane object from the human world with a plaque ‘explaining’ what the monsters speculate it was for – I know this sounds a bit ‘Radio 4’ but they’re really well done), or sometimes just a bench or a kiosk where you can have a cup of tea.

There are loads of other nice little touches, like your monster being able to sit on the shore and dip their feet in the water, the nice solid thud when they try to kick unmovable rocks, and that walking animations can be skipped to zip around solved areas quickly.

Long-time readers of this site may have noticed that I usually focus on two extremes: games that took far too long to make, or games with a strictly enforced narrow scope that have been massively polished within those bounds. AME(TPE) is a great example of the latter, and easy to recommend.

Fall Guys

For a minute, it looked like Fall Guys was going to break through as a cultural phenomenon like Fortnite, but then Among Us (a game which has been quietly ticking along for two years) suddenly blew up, and it was yesterday’s news. I don’t think any analysts could have predicted this sequence of events.

My hat is off to Mediatonic for making such an out-there concept for a game a megahit, and pulling off the coup of getting it distributed as Playstation Plus Game of the Month, guaranteeing the massive player base a battle royale-like game needs out of the gate.

Personally though, I couldn’t get on with Fall Guys and found some of the design decisions inexplicable. The Unity engine gets a lot of uninformed criticism but in the case of Fall Guys it really, really feels like Unreal would have been the more appropriate choice – if you’re building what is essentially a battle royale game, it’s the obvious proven tool for the job.

On PS4, Fall Guys looks weirdly rough, like there’s no anti-aliasing being applied or it’s not working correctly. Long stretches of playing time are taken up staring at loading and matchmaking screens and unskippable stage intros. The argument that the soupy controls and bafflingly constrained camera are intentional choices (it’s supposed to be knockabout Takeshi’s Castle fun where everyone has a chance and skilled players can’t dominate) is a bit fishy when you consider that games like, for instance, Mario Kart manage to achieve this goal while having controls that feel good and reliably convert player intent into action.

But hey, at least it was free. (And for the most part people have stopped calling it’s Twitter account “genius”.)

Doom Eternal

I’ll put my hand up and admit that I made a big mistake and bought Doom Eternal on console, having convinced myself that first person shooters were surely mostly tuned for playing with a joypad these days. Doom Eternal is very much designed around keyboard and mouse. As someone without thousands of hours of Call of Duty muscle memory, I found it manageable for the most part on Normal difficulty, and trivially easy (much like Titanfall 2 on Normal) on Easy. I strongly expect my overall impressions of the game would be more enthusiastic if I’d played on PC.

With that caveat out of the way, is Doom Eternal “not Doom”?

Doom Eternal feels like a 1998 Mega Drive game. (Or, for slightly younger readers: Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas.) id have been tasked with getting bigger, better, more out of the same hardware resources when their 2016 iteration was already pushing things about as far as they could meaningfully go. (The bizarre decision to again include the Switch as a target platform can’t have helped.)

The result is a game that tries to trim away any fat that it thinks the casual player won’t notice. There are more enemy types (and a neat visible damage system) but all the enemy models are less detailed and less expressively animated. Glory kills are shorter (which is welcome in gameplay terms) but quickly become repetitive. The brief, first-person cut-scenes that so economically established Doomguy’s personality in Doom 2016 and which every video and review gushed over? Supporting characters with names and discernible motivations? Totally excised here.

The elaborate heavy metal album cover vistas from the pre-release trailers are intact, but for the most part they’re static, non-interactive skyboxes with the bulk of the levels made up of small, often reflectively symmetrical, nondescript arenas linked together with unwelcome janky platforming challenges. (“Soaring from one planetoid to another in Super Mario Galaxy is fun, but wouldn’t it be better if you had to learn a series of jump and dash inputs by trial and error and then have the game only randomly let you stick to a target wall?” – nobody at Nintendo)

Somewhere in the development process Martin and Stratton wrote “Things that we can add with minimal RAM / GPU cost” at the top of a whiteboard and you can bet every inch of that board was filled. There are reams of superfluous ‘lore’ text. There’s a skill tree and layer upon layer of weapon upgrades and perks. I lost count of the number of buttons on the controller that are eventually given over to different flavours of ‘a smart bomb that mulligans one or more enemy’. (BFG, chainsaw, unmaker, grenades, blood punch, dash attack… it’s been a while, I’m sure there were even more.)

I know a lot of people welcome Eternal becoming a ‘hybrid character action game’, but I’m not a hardcore fan of that genre so it didn’t do much for me. Sprinting around to try to top up different resource meters isn’t as fun as Doom combat.

But, importantly, the Doom combat is still there, under all this needless embellishment, and it’s substantially tuned and tightened up. New movement options like the directional dash and grappling hook make it hard to go back to Doom 2016.

It’s been clear from the past few ‘id renaissance’ games that they’ve typically focused on specific classic id titles to inform the design of each new one. In Doom Eternal’s case Quake III Arena seems to have been a major influence, with lots of jump pads and verticality to the combat. The influence is even apparent in the game’s art style, with lots of bare metal architecture evoking id Tech 3’s ubiquitous cubemap shaded steel. (Doomguy’s space fortress that you visit between levels would be right at home in Q3A.)

In terms of writing and tone, I think id didn’t learn the right lessons from the surprise mega-success of Doom 2016. There’s the aforementioned airport bookshop carousel’s worth of awful flavour text. It’s also very apparent that the writers were inordinately pleased with two or three (not actually that good) meme-ish jokes from Doom 2016 (“Rip and Tear”, “Mortally Challenged”, “Doot”, etc.) which are run right into the ground here.

Doom 2016 still had a bit of a gritty, grimy edge to it’s gore (an echo of Doom 3), whereas Doom Eternal seems to push for a much lighter, cartoony approach. Case in point, most of the demons’ eyes now have pupils and pull silly faces while being pummelled. You’re no longer fending off creepy, relentless deadites – it’s more like smashing rubbery muppet piñatas.

I don’t really see the logic of this change, unless it was focus-group driven. The game is still full of blood and guts, still carries an 18+ rating, and the enemies being fantasy creatures already gives the artists extra leeway to amp up the carnage, so why water it down? (To it’s credit though, the game now gives you the Berserk power up exceedingly rarely, so that set of hilarious, gloriously over-the-top custom death animations retains it’s power to surprise and delight.)

What else was on that whiteboard? Doomguy speaks! Hell comes to Earth! Doomguy goes to (slightly ambiguous so as to not scare Walmart) Heaven! There’s still a Switch port for some reason! Collect vinyl toys! It’s all a bit ‘Gremlins 2‘, but then I suppose lots of people like Gremlins 2.

I realise the above sounds mostly negative, but there are still plenty of things to like about Doom Eternal – it was starting from a high peak with Doom 2016, and in spite of everything Eternal is still at the higher end of ‘good’, in the top bracket of single player FPS for the generation, if not quite hitting ‘great’.

So it Doom Eternal “not Doom”? Interpreting it as a power fantasy is a fatal misreading of the original Doom. Doomguy was meant to be the player in extremis, no match for the forces of hell but sufficiently well armed to – maybe – hold them at bay for a while. (The whole ‘space marine’ thing was to explain why you were there, and why you could carry and expertly use eight weapons and sprint at 70mph.) You’re not supposed to be Master Chief, you’re not some brooding Warhammer 40K demigod.

Doom’s tagline was “where the sanest place is behind a trigger”; Doom Eternal’s is “the only thing they fear is you”.

I still harbour a vain hope that they’ll park the franchise again for a while now, and in a few years we’ll look back and see this incarnation of Doom as a weird anomaly (kind of like Wolfenstein 2009); an offshoot from the mainline Doom games that stand apart as the ones you couldn’t mod and that were never scary.

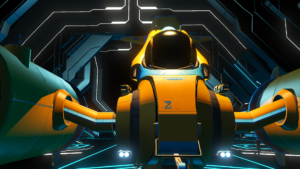

No Man’s Sky (again)

I am, of course, still playing No Man’s Sky regularly. There have been scads of new content and features added since last year, including crossplay, instanced dungeons, massively improved base building, gorgeous new bloom lighting and a big injection of new flora, fauna and planet types. For the first time in a while the game is in a state where I can confidently say that there’s lots of phenomena that I’ve not yet encountered. (I’ve only once and fleetingly seen a sandworm, for instance, and I’ve not found any wild robots yet.)

As a console player, I will of course be upgrading to a next-gen machine at some point in the future at which time I’ll take advantage of the most recent round of improvements to scene complexity and loading times. I’m finding that I’m not that enthused by the prospect though. It’s the same game underneath the higher framerate, resolution and draw distance, and even with all the updates it’s starting to show it’s age a bit.

Seeing people’s PS5 screenshots feels a bit like when you got a whizzy new GPU back the day and ran Quake II with everything maxed out, you know? I’m more interested in what Hello Games do with their tech in future projects now that the next gen consoles’ super-fast storage (presumably) opens up much greater possibilities for more detailed (and more persistent) world simulation.

Noita (again)

Noita finally came out of early access in October. Everything I said about the game last year still holds true, except now there’s vastly more new spells, monsters, biomes and secrets to explore. I’ve now completed the game a few times and am happy with my approach to playing it which has fallen into a pattern (much as it did with Spelunky), mostly involving spending a lot of time crafting wands in the early areas and getting killed through misadventure.

I know there are players who have taken a much more serious approach to the game, curating saves and good random generation seeds to master it’s various mysteries and achievements, but I’m still happy to play it like an arcade game (because it is one), accepting the outcome of risks and randomness. (Oh and I wrote a song about it.)

Cyberpunk 2077

I started playing Cyberpunk 2077 at launch last month, and I’ve just finished my first (fairly exhaustive, 100 hour plus) playthrough. It’s pretty obvious now that people have had a few weeks to acclimatize that 2077 is an important game, setting a new benchmark for open world RPGs in terms of world design and story presentation.

The badly fumbled launch and the misguided attempts by the gutter end of the specialist press to frame the game as some kind of lurid exploitation piece before they’d even played it (why would a major AAA studio, with a coveted cult classic IP, need to court a fringe audience of edgelords?) will mostly be forgotten by Summer. Nobody cares these days how poorly GTA V ran on seventh generation consoles, or the narrowness of No Man’s Sky version 1.0’s feature set. A few people may eventually look back and cringe at how they carried on online in their student days but that will be about it.

I’m playing on PS4 Pro. It’s… tolerable. It still sometimes crashes (though dramatically less often with each patch up to 1.11) and the UI is ‘cantankerous’ if you try to do something unreasonable like open a menu or switch cameras in a car. I’m profoundly aware that I’m not experiencing the game as intended (and in due time will seek to rectify this), but the quality of the craftsmanship is such that the game rarely becomes a struggle to control or looks objectionably ugly.

At 1080p the character models are more than detailed enough for the performance capture scenes to reel you in (the occasional glitching cigarette aside), and the dynamic lighting and level of detail system keep the outside world moving at a decent clip (at least when on foot), and from time to time offer up a genuinely beautiful composition. Shadow of the Colossus on the PS2 would be a good point of comparison. It’s not liquid smooth, and it’s running the PS4 as ragged as the Bluesmobile, but it’s managing to conjure an affect that shouldn’t even be possible on such modest hardware.

(Oh no, cars and NPCs sometimes disappear when I turn around, to absolutely zero gameplay effect, in this game that is being required to support a hardware baseline with less computing power than a modern phone. If you think this is evidence of poor design decisions, follow better YouTube channels.)

As nothing can be discussed on social media without it being categorised as perfect or a catastrophe, Cyberpunk’s problems on the base consoles have been blown up into absurd claims about the underlying game being “fundamentally broken”.

Yes, there are some rough edges, but it’s not a comparable situation to a typical Bethesda open world game, where you’re practically required to use third party mods to finish work on the UI before you can play. It’s not like the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games, my lasting memory of which was having to use a FAQ to know which of game’s prompts had to be ignored to prevent the game falling into an unwinnable state. We’ve grown accustomed to open world games running flawlessly by Ubisoft cranking out another shiny but mediocre one every year. Cyberpunk 2077 is an open world RPG, though, and it’s reaching a little higher.

The trade-off for putting up with being intermittently needled with jank is an astoundingly immersive game world. Given the choice between a game like this and another slick but hollow action/adventure game like God of War or Spider-Man and I’ll pick flawed but ambitious every time.

In terms of gameplay Cyberpunk 2077 is an XXL Just Eat takeaway pizza. It’s unashamedly trashy, 8/10 comfort food in the same way the bulk of Batman Arkham Knight or Breath of the Wild were, except with higher production values (and far less copy-pasted filler content). The core of the game is dealing with discrete missions by applying a loose mix of stealth, hacking, shooting, melee combat and (much more rarely) negotiation, like a two-fisted blend of Deus Ex HR/MD and the Mafia trilogy, with the odd bit of driving, adventuring or private detective work thrown in.

Many of the game’s systems are streamlined to minimise time spent failing missions for pedantic reasons (and to an extent discourage save scumming). Hacked security cameras stay hacked, and you have a couple of seconds to react if one spots you before the alarm is raised. There’s a global switch that stops you being able to outright kill anyone with your attacks (although explosions and other world hazards can still be deadly) if a mission calls for it, so you’re never boxed in to using stealth takedowns if you don’t feel like it.

Unlike Deus Ex, gunplay actually feels good here, pistols and revolvers particularly striking a good balance between being crazily overpowered hand cannons and requiring just enough skill to make dealing with groups of enemies at close quarters a bit hairy. The minigun you can sometimes obtain mid-mission (but can’t keep all the time, sadly) makes you feel like you’re fucking ED-209. The sniper rifles are just ludicrous. It’s definitely the case that you can become too overpowered in combat and/or hacking fairly early in the game taking away most of the challenge, but you can always turn up the difficulty level or set your own limits on your playing style (or use mods) I suppose. Outside of some stealth-heavy or booby trap laden areas, it’s never a particularly stressful experience.

The ‘main quest’ story missions are tense and exciting without ever doing anything mindblowing. (The in-engine montage cut-scene at the end of the prologue with a flurry of jump cuts is pretty cool though.) The scope is genuinely impressive, with different storylines taking the player to wildly contrasting parts of the game world and presenting them with characters and situations that let the player express more facets of their character and learn more about how Night City’s society fits together. The movers and shakers in NC variously see the player character (V) as an uncultured outsider, a useful asset, a potential threat, or an easily manipulated mark.

While there are obviously ‘tiers’ of quests ranging from expensive-feeling cinematic adventures to more mundane mercenary gigs (you can usually grade these by ‘amount of Keanu Reeves involvement’), a surprising amount of the game’s content falls into the former category. Some of the side stories (as well as the main story in Act I) change tack as deftly as a golden age Simpsons episode. Anything from taking on a gun for hire contract to ordering a coffee to wandering around a market can lead to an unexpected side story kicking off.

The main story (your character, a small-time mercenary, or ‘punk’ you could say!!, gets involved in a heist gone wrong that results in their mind being merged with a neural construct of a long-dead anarchist rock star, and has to find a cure before their personality is overwritten entirely) is impressively executed. The combination of lighting, character models (with fancy dynamic lip syncing tech), voice and performance capture often leads to strikingly naturalistic scenes. (Compare the first encounter with ripperdoc Viktor Vektor with the equivalent scene in Deus Ex Mankind Divided to see how far we’ve come.)

There’s been so much focus on glitches in the traffic and crowd systems that a lot of people seem to have overlooked all the hard technical problems Cyberpunk does quietly solve. There are (for instance) several sequences where multiple characters will get into a car and carry out a fully animated conversation while driving around the city, without the game ever breaking out of the first person view. The extended scene with Jackie and V going to do a deal with the Maelstrom gang from the ‘fake’ E3 demo is incredibly closely reproduced.

The writing on the other hand is probably not going to win many awards. There are memorable lines and side characters, but the main cast (Jackie, Rogue, Johnny, etc.) are sketched a bit thinly. Keanu Reeves does his best with the material but as voice artists go he’s no Mark Hamill. Silverhand’s cynical ‘fuck the man’ commentary peppered throughout the game is often closer to Rik from the Young Ones than Neo or John Wick. Still, it is refreshing to have a mainstream game based around a different dynamic for the two main characters than Sad Gruff Dad and Escort Mission Child.

But even if there was only a tiny fraction of the big budget ‘cinematic’ content that there is in the game, Night City would still be captivating to explore all by itself. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s the next leap in creating a convincing sense of place in a game, up there with S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and Half-Life 2. It’s still nowhere close to the scale of a real world major city, of course, but it’s unbelievably, overwhelmingly dense within its few cubic kilometres. It’s like Bloodborne dropped into a petri dish the size of San Francisco.

There are walkways over rooftops over elevated streets over streets at the bottom of Kowloon-esque urban canyons where the sky is barely visible, with separate ‘bottle’ maps (reached by loading pause elevators) perched high in the towers and arcologies above all that. And that’s just the inner city. There are miles of desert wasteland, sprawling solar and hydroponic farms, brownstones, motels, slums, suburbs, abandoned malls, forested hills and man-made mountains of trash.

There are buildings and neighbourhoods used for perhaps one throwaway gang skirmish that are bigger than Deus Ex’s version of Prague, and they nearly always have a few unique touches. A lot of locations are built from snapped together components but the sheer amount of assets hides this well most of the time. (There are dozens of bathrooms in Night City, and no two of them look even slightly the same. This dedication to presenting endless diversity to avoid breaking immersion extends to food and drink, weapons, clothes, crafting items and even vending machines and laptops.)

The first few hours of the game are total information overload with hardly a moment to catch your breath. Even once you’ve spent many hours in the game, gained some street smarts and have mopped up most of the available side gigs, you can still spend hours just wandering around the city and finding entirely new (often huge and meticulously detailed) areas, some of which seem to exist for no other reason that game tourism. It feels like CDPR’s level designers have hit some critical mass of having a huge library of assets and a workflow that allows spaces to be built and decorated rapidly.

We’ve all seen Blade Runner, Ghost in the Shell, Robocop, Demolition Man, Akira, The Matrix and Back to the Future II, so by now the visual language of cyberpunk is extremely familiar. But by showing a whole world operating under those rules (including – especially – the mundane day to day stuff) 2077 still sometimes has the ability to surprise.

A street gang who fetishise extreme, dehumanising cybernetic implants is a cool concept as a few pages of an RPG rulebook, but having them get up in your grill in a tense arms deal or going to one of their parties is something entirely other. We’ve seen lots of games with decaying, abandoned urban environments since Half-Life 2, but seeing a bustling city choked with garbage and squalor drives home the desperate state of the situation. Outside of the pristine Corpo Plaza, the spoiled parks and leisure areas of Night City are really viscerally unpleasant!

The game may not be a sophisticated commentary on inequality and corporate power, but it is an unambiguous one. It’s fair to say that the game doesn’t delve too deeply into the more weighty implications of its themes, but it does sometimes dabble in real-world parallels (AI, healthcare, ecology, private policing, human trafficking, cryptocurrency, access to justice, etc.) – it’s mostly concerned with the world at street level, outside of one thread of the main story.

This is a very late-1980s vision of the future, as the source material dictates, although CDPR have wisely omitted or rethought some of the more dated aspects. It’s hard to fully gloss over the streak of anti-Japanese sentiment that is present in most 1980s cyberpunk media, but 2077 is at least self-aware enough to not revel in it. (It has to be said that some of the Asian characters in the game are still a bit stereotypical though.)

I know that games have gone from being a techy niche to a mainstream entertainment medium in the past twenty years, but it’s still been jarring to me to discover that there are so many people out there who seem to not see the prospect of an open world cyberpunk game as implicitly compelling. And by ‘implicitly compelling’ I mean the Holy Grail the medium has been building toward for the past few decades. (And is still building towards, as let’s be clear, Cyberpunk 2077 is far from perfect.)

The dream of CRPGs in the 1970s was to simulate Dungeons & Dragons, the dream from at least the late 1980s has been to let you live and make choices in the world of Blade Runner and Neuromancer. This is most clearly illustrated when we look at the choice of subject matter that so many high profile designers gravitated towards as soon as they had a few hits under their belt and were given a blank slate: Syndicate, Deus Ex, Blade Runner (of course), Beneath a Steel Sky, Snatcher, Interphase, the cancelled Trinity and Cyberspace, even Final Fantasy VII after a fashion were all attempts to realise this dream with the technology then available.

Maybe it’s an age thing? It’s hard to imagine someone who played Sim City 2000, Syndicate and Doom for the first time within a few months of each other as an impressionable teenager in 1993, with a cultural diet of MTV, anime on VHS, 2000AD and Games Workshop could imagine that games were ultimately building toward anything else. Every big technical advance was being measured in relation to reaching that end point. At some point we must have stopped explicitly voicing this desire, and people who have come into games later have simply not picked up on it, which is why the feverish level of hype must have seemed strange.

At certain points when just drinking in the atmosphere of Night City for hours at a time, it has occured to me that this must be what being pandered to feels like. As AAA game budgets have gotten bigger and their subject matter has had to become more broadly appealing, I’d pretty much given up on seeing a game of this scale have a setting and subject matter I really cared about. I can see why, say, The Last of Us or Red Dead Redemption 2 or Grand Theft Auto or Call of Duty have fan followings, but I’d long been resigned to the fact that (with a few exceptions like the modern Deus Ex games) game settings were something to be more or less put up with while focusing on any mechanical interest that they allow.

(Star Wars fares a little better, but you’re always conscious of the fact that you’re playing a piece of merchandise. The characters are too ubiquitous to let you have any feeling of personal ownership over them.)

Cyberpunk by comparison lets the player spend most of their time doing things they care about and that are narratively and/or aesthetically rewarding. You can specialise your character to a much greater degree than in Deus Ex (e.g., going so far as removing the ability to quickhack entirely if you favour close quarters combat), and spend hours picking their outfits and tinkering with the specs of their weapons and cyberware. Every car and building looks like something out of the wildest Syd Mead concept art, with the satisfying material solidity of the coolest Matchbox car or science fiction vehicle playset you had as a kid.

Aside from most of the generic ‘fixers’ who dish out low stakes missions in each district of the city, most of the major characters are either cool badasses who you’ll want to help and impress, or awful dickheads who you won’t feel bad about crossing swords with or just flat out walking away from (very few quests in the game are mandatory and there’s so much content that you won’t feel shortchanged if you choose to skip some of it). (This goes for the game’s factions too – depending on your route through the game you’ll likely end up sympathising with some and having abiding grudges against others.) There are loads of secrets and subtle bits of worldbuilding, and endless diversions included for their own sake (adopt a cat, ride a rollercoaster, befriend various abberant AIs) that make the world feel more human.

Both the game engine and the world they’ve built on it feel like they have a lot of untapped potential. I really hope that along with the slated DLC we will at some point see more stories told with these resources (something farmed out to another studio in the manner of Fallout New Vegas perhaps).

A final thought on the messy launch: if we’re to expect ‘mid-generation’ console hardware refreshes again in future, I really hope that the manufacturers make a more decisive commitment to establishing them as the baseline well before the end of the generation. Nintendo figured this out with their pre-Switch handhelds (e.g., the New 3DS), offering substantially upgraded hardware every few years that didn’t strictly enforce backward compatibility for new games.

Sony seemed terrified of the thought of splitting the PS4 platform, even as later games started to run progressively worse on the base system, and disc sales became less important. There should have been PS4Pro exclusive games on day one, really. Microsoft just made the Xbox One X too expensive to be the logical upgrade route for most players, even though it was five times more powerful. (Plus they’ve shifted focus to Game Pass.)

The model of requiring all developers to support 7+ year old hardware, at considerable cost (Microsoft essentially burnt a couple of years of John Carmack computing time requiring RAGE to run from the DVD on Xbox 360 – a requirement they dropped anyway not long after!) is clearly not sustainable. I wouldn’t be surprised if CDPR had been lobbying behind the scenes to have the rules changed for years.

We can moan about this but at the end of the day publishers have to play the ball as it lies. A blockbuster multiplatform release at that moment in time had to support those machines, and the announcement and release of the next gen consoles started the clock on how long a game built around last-gen expectations could launch as a competitive product. Delaying into 2021 was never on the table. CDPR are part of the way out of the woods, but it was their management decisions that got them into this mess. They still have to convincingly deliver on their roadmap, and they’ll rightly face renewed scrutiny over their policies regarding crunch from now on.

Right now I’m happy that I’ve had my money’s worth out of the game, and I’m looking forward to: playing through again on better hardware (and making different choices), the arrival of the DLC promised for this year, and Tim Rogers’ definitive Action Button Review of the game (even if he hates it I expect to learn something interesting – I highly recommend the ones he’s filmed to date).

Tags: A Monster's Expedition, CD Projekt Red, CDPR, Cyberpunk 2077, doom, Doom Eternal, DotEmu, Draknek, Fall Guys, game title, Guard Crush Games, Hello Games, Horace, Id Software, LizardCube, Mediatonic, nintendo switch, nms, No Man's Sky, noita, nolla games, Paul Helman, PC, playstation 4, sega, Streets of Rage 4