“Resident Evil 4, to sum up, is the best game on the GameCube.

But it’s not just the best game on the GameCube.

It’s the best game of this generation, it’s the best game-“It’s the best game.”

Robert Florence, Consolevania Series 1 Episode 7

It’s easy to be cynical. These days, when any moderately entertaining game with a big enough marketing budget is hailed as the Game of The Year, superlative-spattered reviews start to ring hollow after a while. Which makes it all the sweeter when a game like Resident Evil 4 comes along. Look the game up on Metacritic, and you’ll see review after review desperately trying to salvage some semblance of sober objectivity through the use of trepidatious and insincere qualifiers. “Best survival horror game”, “best GameCube game”, “one of the best”, “possibly” – no. It’s the best game. Even now, two years later, it’s fair to say that Resident Evil 4 still represents the state of the art.

Resident Evil 4 presents a fresh new model for action games, while respecting classic game design sensibilities. The game has a comfortable, familiar feel which has more in common with classic arcade action games such as Ghouls ‘n’ Ghosts than any of the previous Resident Evils. It’s a timeless formula: slow, steadily progress through varied, interesting scenarios at the macro scale, while ‘jamming’ with a fluid, tactile control system in each micro encounter. It gives a game a groove – a characteristic shared by Streets of Rage 2, Wonderboy III, Super Metroid, Castlevania Symphony of the Night and countless others, including your favourite game. Probably.

But Ghouls ‘n’ Ghosts is the game it brings to mind again and again: each area is completely different from the last; movement is deliberate and precise; you can pretty much survive two serious attacks; hell, you even occasionally break open containers and get attacked (albeit by snakes rather than magicians). Though thankfully Resident Evil 4 isn’t quite as unforgiving as it’s forebear.

Resident Evil 4 isn’t really a game about narrative. It has a premise which serves as a framework for presenting the player with a lots of cool, just-about-plausible and internally consistent stuff to do, which is how it should be. The characters are fairly one-dimensional (but deftly designed within the confines of that single dimension), and the script is packed with big, dumb melodramatic moments and cheesy dialogue. The game isn’t interested in messing with your head with oppressive atmosphere and psychological tricks (see Silent Hill, et al), instead opting for a mix of rollicking action and hokey body horror, as might result if Indiana Jones were to gatecrash a seedy 80s splatter flick.

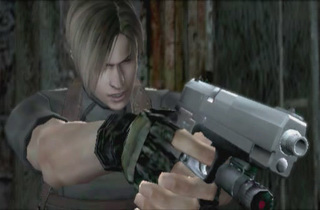

The player is put in the role of Leon S. Kennedy (previously seen in Resident Evil 2), a brash young government agent tasked with investigating the disappearance of the President’s teenage daughter, Ashley Graham. Leon’s search leads him to a village in a remote part of Europe where she was last seen. (This is generally thought to be Spain, based on the architecture and language used, but is never officially referred to as such by Capcom.)

On arrival, Leon quickly finds that the inhabitants of the village have been turned into mindless, bloodthirsty savages (referred to in the game as Ganados, Spanish for ‘cattle’). They’re not zombies – they’re alive and still have sufficient cognitive functions to speak, organise themselves and use tools. They’ve also developed a taste for killing and eating outsiders and a laissez-faire attitude to self-preservation. As Leon makes his way through the village and surrounding area, he learns that the villagers are in the thrall of a mysterious cult leader called Lord Saddler who had kidnapped Ashley to further his own nefarious ends. As the game progresses, Leon gradually discovers more about the source of Saddler’s mind-controlling powers (Las Plagas) and the unspeakable horrors it has unleashed, and crosses paths with a few other interlopers with their own agendas.

Resident Evil 4 makes a clean break from the “survival horror” formula laid down by the previous entries in the series. The static camera angles, awkward controls, and drip-feeding of crabbed, panic-inducing encounters, staples of the genre that have gone unchallenged since Alone in the Dark, are no more. In their place are the workings of a slick, modern third person action game. Combat is now more often cathartic and empowering than a desperate battle with groggy controls (which isn’t to say that the demands of “survival” are any less acutely felt). Environments are wide open and invitingly interactive. The action is carried forward through a composition of cinematics and novel situations woven together with the effortless confidence of a development team in complete control of their craft.

The game is able to layer on so much rich and varied content thanks to some very bold decisions about the design of the interface, which laid exceptionally solid foundations for Capcom’s planners. They realised that while the classic Resident Evil interface had to be abandoned, the most obvious alternatives (the standard ‘dual stick’ systems used by console FPS and third-person action/platform games) weren’t suitable either. Therefore it was necessary to create a new system, combining turning on an axis (as opposed to strafing – think Tomb Raider rather than Super Mario 64), sensitive cursor-based aiming, and an eye level over-the-shoulder camera which allows the player to be aware of the relative position of Leon while having a clear view of (and shot at) nearby and distant enemies. Leon can’t attack while moving, so when the player holds down the right trigger button to ready his weapon, the controls and camera become fully dedicated to aiming and firing.

All the game’s content has subsequently been designed and rationalised based on exploiting the strengths (while downplaying the weaknesses) of this interface. Most of the enemies Leon faces are quite slow moving, slow to react, and armed with rudimentary projectile weapons at best – but they generally take a lot of shots to neutralise, and attack in groups. The player quickly learns that the real hazard in the game is getting surrounded, as Leon’s weapons are dramatically less effective at short range, and the Ganados’ melee attacks nuke Leon’s health and leave him prone for seconds at a time. Another neat instance of this design is that the plot stipulates that the baddies are trying to capture rather than kill Ashley, removing a lot of potential frustration from the escort mechanic at a stroke.

A lot of the reason that this doesn’t leave the player feeling hopelessly vulnerable and frustrated is down to the weapons being such an utter joy to use. This is one of those modern games where pistols continue to be useful even after the player has got their hands on the shotguns, uzis, rifles, grenades and rocket launchers. They’re varied enough to make it possible to play the game in very different styles depending on your preference. I won’t describe them all in depth beyond saying that the shotgun is easily the best shotgun in any game since Doom, and all of the other weapons are at a similar standard.

So this is all well and good for traipsing around and shooting things, you may be thinking, but surely if Leon can’t strafe, jump, duck or dodge at will he must surely be like the player characters in the previous Resident Evils – a cumbersome walking tank endlessly ice-skating against walls and generally being thwarted by his environment? Not so. Leon’s repertoire of moves is extended massively through the use of a context-sensitive action button. This button allows the player to (among other things) jump through windows, kick open doors, knock down (and raise up) ladders, leap gaps, Give, Pick Up, Use, Open, Look At, Push, Close, Talk to and Pull (hmm…).

At certain points in the game, there are ‘action events’ (much like the Quick Time Events in Shenmue) where a combination of controller buttons will flash up on screen, and the player must quickly hold them down or repeatedly tap them to prevent Leon from being flattened/skewered/eaten/decapitated. In that order. The only other interface elements are the inventory screen (which is completely effortless to use), the map and various status screens showing the documents and treasures that Leon has collected. Oh, there’s also a couple of buttons for issuing commands to Ashley (allowing Leon to leave her in a ‘safe’ place while dealing with the immediate threat).

The lion’s share of playing time it given over to combat situations with small groups (meaning at most dozens, rather than Dead Rising’s hundreds) of intelligent enemies. Every enemy in the game manages to pose a threat. Even the comparatively weak and slow-moving villagers can still surround Leon, catch him unawares with a rusty farming implement or suicidally whip out a stick of dynamite at the wrong moment.

While the combat scenarios are extremely varied in themselves (the player needs to employ significantly different tactics depending on the environment, enemies and objectives involved), they are also punctuated with radically different sections including boss battles, simple puzzles, vehicle rides, timed sequences and treasure hunts. At every turn the player is presented with a substantially new activity, none of which are repeated or outstay their welcome. (A marked contrast to the approach taken by popular airboat simulator Half-Life 2, where each new contrivance was relentlessly forced on the player long after they had outstayed their welcome.)

The game’s boss sequences are an unexpected pleasure. Each is completely unique (foes range from mutated humans to giant lake monsters to T-1000-meets-the-Alien insectoid killing machines) and usually involves some specialised forms of interaction that aren’t found elsewhere in the game and yet feel completely natural. Many also include mini Quick Time Events, for instance requiring the player to quickly press specific buttons to dodge an attack, or to rapidly tap the action button to hack at the boss’s exposed weak point.

Although I’ve been dismissive about the role of narrative in Resident Evil 4, Capcom have done a great job in realising a set of characters and a self-contained Lovecraftian mythology that make it easier for the player to emotionally invest in the game. The game’s story wouldn’t stand on it’s own as a piece of entertainment, but it does a good job of sustaining a tense atmosphere and introducing new elements often enough to keep things from dragging.

Leon’s a great player character, simply by dint of the fact that he’s not yet another smirking, morally ambiguous anti-hero. He’s extremely chivalrous and dedicated to duty, but neatly avoids coming across as a boring do-gooder by being, well, a bit of a nob. Most of the conversations in the game involve him trading witty retorts with the main villains – or at least what pass for witty insults in particularly unchallenging Saturday morning cartoons. (“Huh! Monsters. I guess after this there’ll be one less of them to worry about.”; “Rain or shine, you’re going down!”)

(In the bonus materials of the PS2 and later versions, Ada Wong earnestly describes Leon as “practically a genius”, amusingly.)

Ashley isn’t your typical ‘damsel in distress’ character (or at least not completely), being able to fend for herself and assist Leon at certain points of the game. For large parts of the game Ashley tags along with Leon as an AI-controlled escort, and manages to never be irritating. She doesn’t get in the way when you’re shooting, or run off and get into scrapes, and she hardly ever talks, aside from calling Leon a pervert whenever he inadvertently (ahem) looks up her skirt.

The game’s big boss, Osmund Saddler, is basically Count Dracula. While Saddler is ostensibly the mastermind behind the evil goings-on in the story, Capcom have created a far more memorable villain in his protege Ramon Salazar, the creepy progeriac dwarf Castellan who antagonizes Leon throughout the second act of the game, set in and around his trap-laden ancestral home.

The cast is rounded out with a handful of memorable supporting characters including the mysteriously helpful Spanish sleaze ball Luis Sera (“I used to be a cop in Madrid. Now I’m just a good for nothing guy, who happens to be quite the ladies man.”), femme fatale Ada Wong (another returning character from Resident Evil 2), psychotic mercenary/Metal Gear refugee Jack Krauser, and last but by no means least, The Merchant.

The Merchant is incredible. A nameless freelance arms dealer with a Dick Van Dyke cockney accent (“Wot are ye selliiin?”) and a purple longcoat stuffed with weapons, items and upgrades, he’s encountered in the unlikeliest places throughout the game and is never acknowledged or commented on by any of the other characters. He even operates a chain of shooting galleries in the bowels of Salazar’s castle (offering ‘bottlecap’ action figures of all the characters in the game as prizes). Any other game would have gotten caught up trying to concoct some plausible mechanism for Leon to be able to trade in treasure for equipment, and would have ended up with something less effective (not to mention less hilarious).

I’ve managed to resist waxing lyrical about the game’s presentation up until now because I’m worried that I might not ever finish this article if I start. The game is split into three main acts (the village, the castle and the island), each of which is arranged as a broadly linear series of areas. Through technical wizardry, attention to detail and sheer, audacious smoke and mirrors, Capcom have managed to make all of the varied locations of the game feel incredibly atmospheric and plausible. Scenes that the GameCube (let alone the puny PS2) shouldn’t be able to render are so frequent that you eventually become desensitised, only to dip into your save games at random months later and gawp helplessly. During my current playthrough I’ve picked out the storm outside the church, the Lava Room, and pretty much everywhere inside the castle as standout moments.

Once the main quest has been put to bed, there’s an extra chapter played from the perspective of Ada Wong (which isn’t present in the original GameCube release, unfortunately) which is up to the standard of the main game, although it demystifies some of the events and characters a tad too much.

There’s also the incredible Mercenaries (time attack) mode, which drops the player in an enclosed map where they must fight off endless respawning Ganados before the time runs out. This mode presents a fiendish dilemma: there are time bonuses scattered around the maps, and more time potentially means more kills, but also increases the risk of being overwhelmed. This mode is a masterstroke. Every game plays out differently and there are a bevy of levels, characters and a couple of weapons for the main game to unlock. (The only downside is that one of the levels has a blind spot which can be exploited indefinitely to rack up risk-free kills.)

Due to unfortunate circumstances (the fact that it debuted on a relatively unpopular hardware platform, and the perception of the Resident Evil franchise and adult-themed games in general) Resident Evil 4 hasn’t been heralded as a landmark title quite as conspicuously as some other important games of recent years (such as Doom, Half-Life, Grand Theft Auto 3, Halo and World of Warcraft). It hardly seems to have made an impression on the wider public consciousness at all. (Whereas endless column inches continue to be squandered on the dumb shiny bauble that is Second Life.)

Nevertheless, the mere existence of Resident Evil 4 should give anyone who cares deeply about games a reason to celebrate. Maybe the way the games industry is structured is deeply flawed, and games like this really shouldn’t have to be so rare. But at the very least it proves that there are still good reasons for developers to be allowed to work on big-budget projects – being gifted a comfortable amount of time, money and expertise doesn’t excuse developers for making vehicles for flashy graphics built around derivative, threadbare design.

In an ideal world, the huge swarm of camp followers that has in recent years flocked to the edges of the games industry – the ARG marketeers, the Second Life groupies, the purveyors of gem-matching/restaurant-wrangling casual games, the pen-and-paper RPG bores, perhaps even the contemptible, dead-eyed human fungus responsible for so-called “Serious Games” – would be forced to play through Resident Evil 4 and then consider at length whether what they’re doing, or the directions for the industry they suggest, could ever result in something even remotely this fucking cool.

Ultimately games aren’t about stories, or messages, or artistic worthiness. They’re a device that players can use to mould their own unique experience, and to share their creators’ ingenuity in defining the parameters and potentialities of this experience. They create an imprint on the memory unlike any other kind of media. I’m certain that Resident Evil 4 will stay in the memories of everyone who plays it for a very long time, and will have a lasting influence on action/adventure games to come.

Resident Evil 4 is simply the best single investment that anyone who likes games can make.

It’s the best game.

“Writhe in my cage of torment, my friend!”

– Osmund Saddler, 2004

What you need to know

If you haven’t played the game already, perhaps you should make it one of your short-term life goals? The GameCube version should be your first choice (but see below – time-travelling Ed.) and absolutely justifies the (now presumably quite heavily discounted) cost of the machine. The Playstation 2 port includes some additional bonus features but at the expense of longer loading times, muddier visuals, looser controls and prerendered cutscenes. The core gameplay is largely intact, but the many sacrifices firmly classify it as a false economy.

The belated PC port has been lambasted online for being inferior to either of the console versions, but this isn’t entirely fair. Most of the criticism of the visuals has been based on the original release of the game, which (unbelievably) was shipped with lighting and fog effects almost entirely absent. A subsequent patch brought the graphics back up to a generally acceptable standard, although some of the nicer visual effects of the GameCube version (such as reflective water, depth of field and explosion shockwaves) are still absent.

The patch doesn’t alter the sad fact that this port was based on the Playstation 2 version’s assets, which means that the GameCube’s beautiful real-time cutscenes are once more replaced with 512×336-pixel prerendered junk. This looks even more jarring on a monitor than on the PS2, and is severe enough for me to urge that players steer well clear of the PC version unless they’ve already completed the single player game on another platform. Cutscenes aside, the game plays as well as the other versions, and the higher resolution makes it easier to pick up some of the finer (and grislier) graphical details that are hard to spot on a TV. Naturally, the game does not offer mouse support, and should be played using a joypad. Anyone who complains about this is a fool.

There is also version of the game for the Wii (released later this month in Europe), which combines the GameCube version’s engine and assets with the bonus content from the PS2 port and implements a new control scheme tailored to the Wii Remote and Nunchuk. Early indications suggest this will replace the GameCube version as the definitive one.

So apart from making sure they get the GC or Wii version, first-timers should also be aware that the ‘Easy’ mode actually removes some sequences and areas from the game, and so should opt for ‘Normal’ or above to avoid missing anything. (Other frustration-avoiding tips include: Cover the foetid well before shooting down that shiny pocket watch; don’t sell things without examining them for possible combinations; use the knife to save ammo; and remember that flashbangs kill exposed parasites.)

Enjoy.

Tags: best, capcom, Game, game title, gamecube, multiplatform, resident evil 4, what are ye sellin'?, wii